The Bad News is The Good News

Climate is not our only urgent existential problem, but they all require the same kinds of interventions — sweeping changes with tremendous potential to make your life – and the lives of so many human and more-than-human beings – better… if we can summon the political courage and consensus to support truly comprehensive action to end the fossil fuel era and honor collective thriving.

A few years ago, Heather was nearing the end of her tether with the intellectual-austerity mindset of the administration at her former college. Her patience with the way that their race-to-the-bottom allocation of resources always resulted in climate breakdown education coming in dead last was all but gone. Predictably, she protested yet again. In response, a colleague huffed back: “But don’t you care about human rights?!”

The enormity of the ignorance in that question stopped Heather in her tracks.

While temporarily frozen, she tried to pinpoint the reason that an adult with above average access to information – one who gets paid to think for a living – would draw a distinction there. Was this just the professors at the bottom of the barrel fighting over scraps? Was this just a privileged dude needing to flex his man-mind muscles and show how ‘smart’ he was? Was it a defensive reflex demonstration of his superior level of “goodness”? How could he deny the importance of climate education?

How could he not understand that climate and ecological breakdown are the biggest threats to human rights and well-being? How could her colleague(s) not see that our Earth-system existential crises and our varied and robust human-system crises were caused by the same things? And that solving them all depended on connecting them together? That the Bad News is the Good News? The answer: Because this framing and the responses it requires challenge established institutions, so we rarely hear about any of this.

One of the first things Heather and Nicole bonded over was their shared ability to see the enormous overlap between several kinds of bad news and good news, their shared tendency to find that fact equally sobering and motivating, and their shared experience of working in settings where folks seemed uninterested in grappling with the implications of this bad-good (or good-bad) news. Together, they keep trying to shed light on how deeply connected human and planetary wellbeing are – and to lift up the kinds of transformative changes that have tremendous potential to address both. While we each view the political prospects for such change differently, we both agree that there is value in reframing the problems (widening the lens beyond climate breakdown) and sketching out a bold plan for ending the fossil fuel era.

‘Climate change’ is in the news now nearly every single day, especially since the wealthy world began experiencing the impacts from unmitigated anthropogenic global heating around 2020. It still isn’t covered nearly enough or accurately enough. Most outlets emphasize attention-grabbing doomsday stories – and skip the critical analysis of the human systems driving us towards doom. Others publish banal chatter about degree benchmarks of atmospheric warming or CO2 targets, as if they were reporting on the stock market that day. Both takes result in passive denial: it’s either too late, or it isn’t that serious. This tends to reinforce a few flavors of individualistic business-as-usual, whether that’s abject consumerism and pursuit of personal profit and comfort or committing to living a news-free, navel-gazing ‘simple life’ outside of the mainstream.

Seeing as we’re already entertaining the bad news here, let’s get into the details.

The Bad News

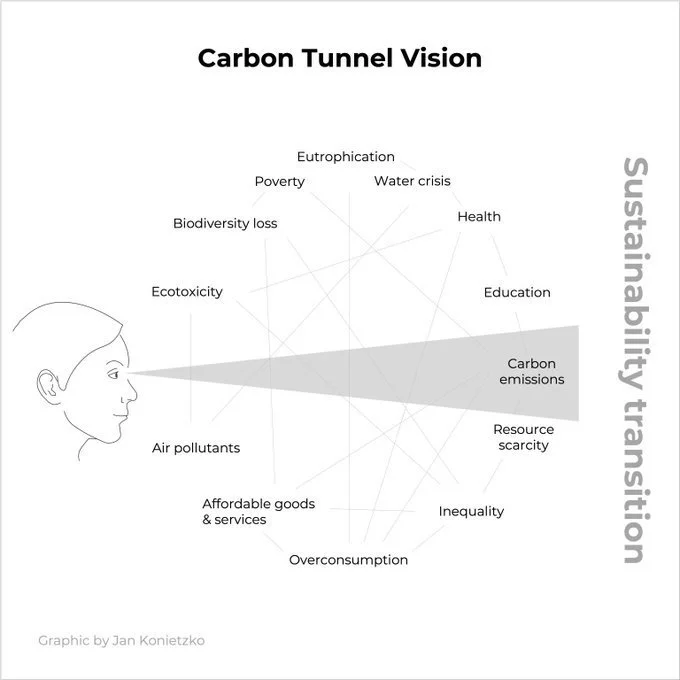

Undercovered though it is, the climate crisis gets far more attention from governments, billionaires, and the public at large than any of the other planetary boundaries that our collective human endeavor has crossed, however inequitably. Solid science demonstrates clearly that we cannot continue to live here – on Earth – if we continue to ignore the planet’s other boundaries. Worse, any proposed ‘solutions’ to climate breakdown that do not involve a rapid and immediate phase-out of fossil fuel use will cause many of these planetary (and human welfare) boundaries to be further transgressed. Outside of academic or some activist circles, few people are really talking about the other boundaries in meaningful ways. To the contrary, mainstream economists continue to contend that the extractive economy can and should grow indefinitely on a physically finite planet. They also tend to accept that the social, racial, and gender violence that enables so much “economic growth” is, if unfortunate, normal, inevitable, and perhaps ameliorated by… more economic growth. .

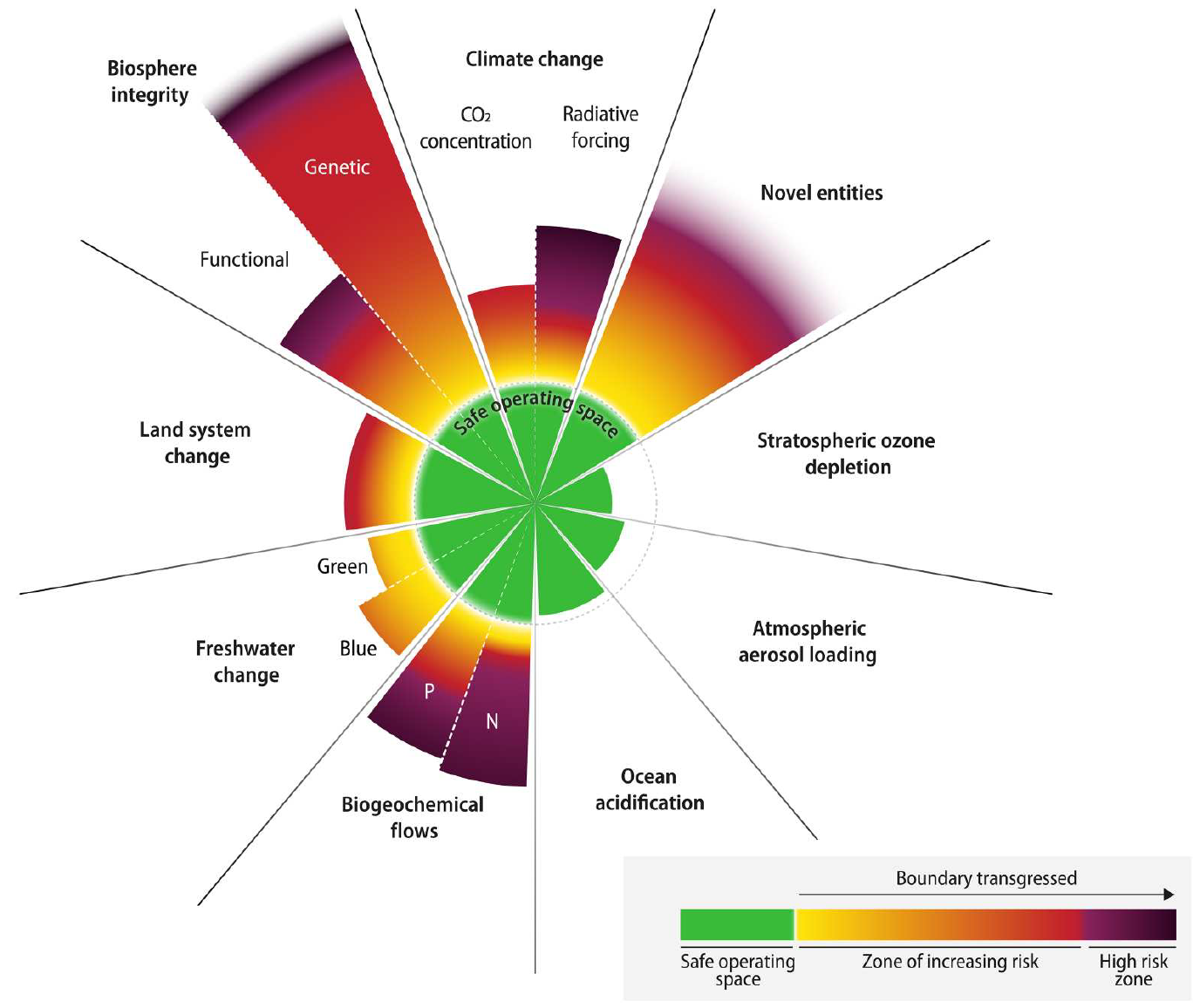

Because the very concept of planetary boundaries has gotten so little attention, we cannot assume that readers have any idea what we’re talking about. So let’s review: The planetary boundaries framework was first introduced in 2009 by researchers at the Stockholm Resilience Centre in Sweden. It was designed as a tool for assessing the health of nine Earth processes and systems that make our planet a stable and habitable place to live for its current residents. These boundaries can be thought of as marking the limits of safe planetary operating space. Surpassing a few of them, by small measures, does not mean the end of the world. But human industrial activity has now caused six of the nine boundaries to be crossed, some to both large physical and temporal degrees, and that is a problem. Johan Rockström, climate scientist and Centre researcher explains:

“We don’t know how long we can keep transgressing these key boundaries before combined pressures lead to irreversible change and harm.”

A stable climate is just one of the Earth’s critically exceeded boundaries. Systems and processes involving the biosphere account for four areas of overshoot:

biosphere integrity relates to the functioning of ecosystems, and was surpassed in the late 1800s;

land-system change, which reflects human land use and encompasses animal and crop industrial agriculture

novel entities, which assesses levels of plastic and other pollution; and

biogeochemical flows, which tracks exchanges between the different spheres of the planet and is tremendously impacted by fertilizer pollution.

The hydrosphere has not escaped human thirst for overuse. The sixth presently exceeded boundary is:

Freshwater change, which measures the cycling and availability of blue water (land reservoirs) and green water (in plants).

Humans are using more than is sustainable in both the blue and green categories, at least in the original sense of the word sustainable (i.e., that which can be indefinitely sustained or continued).

The only planetary boundaries that are not presently surpassed are ocean acidification (and the boundary is close), atmospheric aerosol loading (particulate air pollution, though it is surpassed in some regions), and stratospheric ozone depletion (the ozone hole; successfully mitigated through the 1987 Montreal Protocol).

Six out of nine. That doesn’t sound good. It isn’t good. Because these processes and systems are all connected to each other in complex ways, it is difficult to predict for how long and how far we can overstay our welcome without serious, cascading consequences.

Further, if we actually account for, at least in some part, the unequal human responsibility in over-taxing our Earth systems, then we’ve crossed seven out of eight planetary boundaries for safe and just operating space.

So focusing our political efforts and dialogue solely on mitigating or ‘adapting’ to climate ‘change’ grotesquely misses the point and courts disaster from a physical science perspective. One (perhaps?) obvious danger with focusing on climate to the exclusion of all other boundaries is that we cannot have a functioning climate without a functioning biosphere, and vice versa. There are many feedback loops that link these two precarious systems, for example: plants and other primary producers draw CO2 from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and sequester it in their bodies, which helps cool the atmosphere over short-term cycles. Some ocean organisms make shells by combining calcium with CO2, some of which turns into limestone rock, thus taking the greenhouse gas out of circulation on geologic timescales. If photosynthesis ceased or never began in the first place, we’d have an atmosphere as hot as Venus’s and equally devoid of oxygen.

On the flip side, if climate changes quickly enough, the temperature and precipitation conditions that an ecosystem has evolved to exist within become different enough to initiate wholescale die-off of those photosynthesizers (and everything else that lives there) so that they no longer sequester atmospheric CO2, and may even become a source of it. By some estimates, this is close to happening in the Amazon rainforest. It would be a similar story if the ocean acidification boundary were breached – most atmospheric CO2 is actually drawn down by phytoplankton, who die in acidic ocean water. The ocean is and has been the largest sink for human CO2 emissions. But once the ocean is too acidic to support the life of phytoplankton, it could flip and become a source of emissions instead.

Again, this illustrates the danger of myopic focus on the one planetary crisis that actually makes headlines. But another policy and communication failure is the failure to understand or explicitly call out how many so-called climate ‘solutions’ have the potential to actively harm other already compromised, Earth systems. And if we’re not even grappling with how these supposed silver-bullet tech-based emissions reduction and sequestration strategies might also be terrible for other aspects of planetary health, you’d be right to suspect that we’re nowhere near having serious conversations about how those faux-solutions will also further entrench colonialism, racism, and gross economic inequality in the human realm.

For example: A transition of our energy sector away from fossil fuels and to renewable technologies will require a lot of new materials and metals. Mining and processing those materials results in the direct destruction of intact ecosystems and water resources, and requires a new colonization of the global south, where most of these new resources are. We absolutely cannot afford to sacrifice any more forests or wetlands, divert more rivers, or flood more ecosystems to satisfy the ever-growing hunger for energy among the already economically privileged. Doing so is both inequitable and self-defeating. We would be shooting ourselves in the foot by exacerbating other planetary boundary overshoots. It would also endanger the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous and other marginalized people who have little to no responsibility for existing planetary boundary transgressions, and who are the ones who have been the most effective at stopping them.

Being mindful of, and addressing these past and possible future human transgressions is not just a moral issue - it is a matter of social and political stability. We, as in all humans who wish to continue to live on this planet, need all hands on deck to stop the current breakdown of climate and allied Earth systems, and the resulting biosphere destruction. Stopping this multi-system breakdown will crucially involve an examination of economic, cultural, social, gender and racial privilege when any ‘solutions’ to these crises are proposed. This is what the beginning of a real Just Transition looks like.

We quite literally cannot reduce global CO2 emissions on any meaningful timeframe by any meaningful amount without rich countries and individuals dramatically reducing their consumption of meat, goods and energy, ‘green’ or not. That means me. That likely means you. And such reductions have to be supported systemically – they cannot merely be the result of individual action. Additionally, as the impacts of wealthy nations’ decades-long inaction results in worsening and more frequent heat waves, floods, storms, droughts, and food shortages for the majority of the world’s population, the global north’s strategy of ‘security without peace’ will prove to be the lie that it is already shaping up to be.

So, that was A LOT of bad news. But I hope you are still reading because the good news is actually quite good.

“ Imagine going through your day knowing that everything you do, everything you make, every human gesture, is contributing to making our only home a livable home for all living things, present and future. Imagine the joy that could exist in your lifetime, knowing that you are part of a collaboration of humans bringing a new economic order and new, relational cultures into existence for the next generation and the many to come. ”

The Good News

The good news? The ‘solutions’ to the transgression of all of these physical boundaries, as well as the social-political- economic crises that go along with them, are the same: a careful, controlled but rapid, decisive transition to a steady-state global economy based on equity and fairness. This can be achieved, in part, through the redistribution of wealth. The new economy (or economies!) would focus on meeting everyone’s needs within planetary boundaries, and at the same time, free people’s time and energy so that they can cultivate relationships and enjoy doing good work- not just working to get by. Quality of life for the vast majority of people on the planet would improve, by a lot in many cases, and there would be greater security and real community in a shared sense of purpose. Humans, with and within the natural world, could flourish, and help each other through the ‘natural disasters’ that will still come for many decades, as the climate and Earth systems adjust to a warmer but stable new normal.

Imagine going to work in the morning knowing that your labor, whether physical, emotional, or intellectual, is making the living world and the many lives in it better, rather than making more money for a handful of astronomically rich strangers. Imagine having your basic needs met (and those of your neighbor and of people on the other side of the planet), so that no one has to choose between buying food and heating their home. Imagine knowing your neighbors, trusting them, and participating in direct, open democratic processes with them to shape how you live together. Imagine going through your day knowing that everything you do, everything you make, every human gesture, is contributing to making our only home a livable home for all living things, present and future. Imagine the joy that could exist in your lifetime, knowing that you are part of a collaboration of humans bringing a new economic order and new, relational cultures into existence for the next generation and the many to come.

If we (rightly) frame all of our connected existential human-climate-biosphere crises as being the symptoms or result of a growth capitalist global economic and and neo-colonialist political system that extracts and subjugates, – and we recognize that the existing political economic order is neither natural nor inevitable – the real solutions become clear. System change does happen, and our present system will fail. Economists cannot win arguments with physical reality, though they try. The only questions are when and how system change will happen, and the answers depend entirely on what globally privileged people decide to do about it, collectively. We need to educate adults, and elect politicians who will expand democracy to include citizen’s assemblies, participatory budgeting, and guaranteed universal basic income and services to take the pressure off so that our economic system can be transformed quickly and equitably. (Achieving any of this, let alone all of it, is a tall order, to be sure. But laying it all out can help to get really clear on what we are working toward and fighting for before we deem any effort impossible.)

To be clear: radical and rapid action to stop climate breakdown is absolutely imperative if we want to avoid the immense suffering and untimely deaths of millions, if not billions of animals, plants, fungi, and humans within the lifetimes of many reading this essay. This is not an exaggeration. The simplest, most guaranteed-to-make-a-huge-difference way to do this is for humans to stop burning fossil fuels as soon as possible. (This isn’t the only thing we need to do, but it will have the biggest, fastest beneficial impact in terms of climate stabilization – and it will open up some space for the other kinds of changes in how we show up and how we treat each other that must follow.)

Breaking up with fossil fuels over very short timeframes would require a series of carefully-planned steps. Ending the fossil fuel era begins in rich countries with:

Nationalizing the fossil fuel and energy industries, just as we do for other essential services like the postal service and health care (in most wealthy countries except, disastrously, the United States). Nationalization of this sector allows for the phase-out of fossil fuel use in line with scientifically-based schedules without having to do battle with the huge propaganda machines from those astronomically wealthy people who just want a more for themselves, livable planet be damned.

In parallel, we would need to quickly reduce excess energy demand by scaling down less-necessary parts of the economy, such as luxury goods’ production and consumption. We would, instead, focus economic production on what is required for human well-being and ecological & climate stability. This would involve emphasizing and incentivising the production and trade of quality goods that are durable, repairable, and repurposable. Material culture and production would no longer be primarily for the purpose of generating corporate profits and stimulating insatiable privileged consumption. There are an array of law and policy mechanisms in and beyond the tax codes (e.g, production levies, luxury taxes, right to repair laws, mandatory return and life cycle regulations) that can be implemented to drive such a shift. But this isn’t only a top-down, public sector-driven effort – this is a place where both meaningful shifts in corporate purpose and culture and changes in the tactics used by advertisers are needed. It also involves individual behavior change – not about buying purportedly greener products, but actually ignoring trends and buying A LOT less stuff.

Protect people by establishing a social foundation through the provision of basic income and services (mentioned above). This includes universal public healthcare, housing, education, internet, transport, water, and energy. As numbers 1 & 2 are realized, the workweek will need to be shortened and jobs shared, so that everyone can be guaranteed meaningful work if they want it. Universal income can top up wages, so that everyone has what they need to live a decent life. As Jason Hickel says, universal basic income and services are “the bread and butter of a just transition.”

Pay for all of this by taxing the rich out of existence (or even just fairly), with wealthy governments issuing currency to prevent inflation as this transition settles. It is well-established that cutting the purchasing power of the rich is the single most effective way to quickly cut global CO2 emissions and excess energy use. It is also well-established that the wealthiest among us are presently putting (nearly) nothing into the collective coffers, while the rest of us contribute a substantial percentage of our income. Now, before you reflexively laugh this off and sneer “that will NEVER HAPPEN”, let’s remember that it has before and it can again. Further, there are already wealthy individuals organizing and demanding that the world’s governments tax them more. Wealth taxation – its merits, mechanics, and the path to making it a reality – deserves much deeper exploration than can be squeezed into this list. Those who find the idea of ending extreme wealth alluring but amorphous and frustratingly out of reach might consider serious proposals for a fair-share wealth tax and maximum income policy. (There’s even a current proposal for a fair-share tax in EcoGather’s home state of Vermont, championed by some of our allies in the Vermont Prosperity Project.)

Transition on the scale needed to achieve our climate and ecological goals will require a massive public mobilization. We need to transition all of our necessary fossil fuel infrastructure to renewables, and in such a way that most people use a lot less energy overall. This will require a lot of labor – winding down, ramping up, retrofitting, repurposing, and re-skilling. This is where people who used to work in fossil-fuel-dependent industries – as well as in jobs related to excess and luxury consumption – can be retrained and offered climate-supporting and life-servicing jobs instead. This should be done of course, while being mindful of international climate and environmental justice.

Lastly, we need a strong commitment on the part of rich countries to climate reparations to poorer countries and the global south. Wealthy countries and individuals are such largely because we’ve profited off of the pilfering of the resources and bodies of the majority of the planet’s population, both human and more-than-human, as well as the atmospheric and ecological commons that we all rely on. This should include debt cancellation, technology transfer, and direct grants.

The sum of these steps results in the human endeavor putting more resources into creating the conditions for life to thrive, rather than toward extraction, domination, destruction, and war. Numbers 1 & 2 would require the scaling down the global military industrial complex, as it contributes more CO2 to the atmosphere than many individual industrialized countries. (Not so fun fact: those military emissions are exempted from reporting to the COP accounting process - so they are not even counted in authoritative emissions data and reduction plans). Numbers 2 & 4 would immediately take the pressure off of already disabled Earth systems and ecosystems. Numbers 3 & 5 would provide people with resources, purpose, and solidarity - the foundations needed for building strong relationships and community across difference. We would expect to see fewer divisions, and less ability to escalate them into the human catastrophe unfolding in Gaza (and too many other parts of the world) right now.

This all, of course, will require us to elect political representatives who get it - who understand the existential nature of the crossroads that humanity and the living world are stood at, and the enormous responsibility and opportunity that we privileged have right now to get things right. Our elected officials would also need to be uncommonly courageous and more concerned about accomplishing the above than about their own re-election prospects.

Admittedly, the political landscape looks bleak right now in that regard (particularly in the United States), and we are quite short on time. We can (and will) debate about which forms of political organization will be best able to cohere, scale, and enable coordinated action and expand the universe of the politically possible. But we must remember two things: (1) this is a time for clear demands and committed action; and (2) there is no near-term deadline after which this struggle becomes entirely pointless. Earth systems don’t work that way. Neither do human ones.

The sooner we act, the more suffering we can avoid. The bolder we are, the more we can improve the lives of those already struggling. Conversely, the longer we wait, the more impacts from bad things we’ll have to deal with even after we’ve established the good things. Moreover, constantly coping with major disruptions does make it tough to build momentum on the work that most needs doing. Disruptions will continue – and we will need some folks devoted to response and recovery work when they do. So, as we shift the kind of work that is prioritized by societies and economies in transition, we should also make sure that we’re staffing for both response/recovery and transformation.

This is the struggle of our lifetimes, perhaps of all lifetimes, ever. And it is worthwhile. We need things like the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty to be adopted by rich countries so that we can implement the steps above without governments’ fear of disadvantage for being early change-makers. Why not a wealth-cap treaty?

We also need to tell new stories about how our lives can be different, collectively, in the very near future. Motivated by those stories, we’ll need to either become, support, or elect the people needed to make that meaningful change. We need to recognize that our apparent racial, gender, and ‘culture war’ differences are constructs invented to divide and conquer, and only help those who benefit from the status quo. We need to forge alliances between us - especially between labor unions and climate and environmental movements so that we can organize and withdraw our cooperation from an unjust system to compel change. And we’ll need to begin living differently.

This is hard work. And it is worthwhile.

In sum: the radical, necessary, re-organizing of the global economy will simultaneously stabilize the climate, pullback our other planetary boundary overshoots, enable billions of people to meet their basic needs, and begin to address our intersecting human crises. While it requires sweeping shifts, the shifts outlined offer us a way through our present despair and future catastrophes.